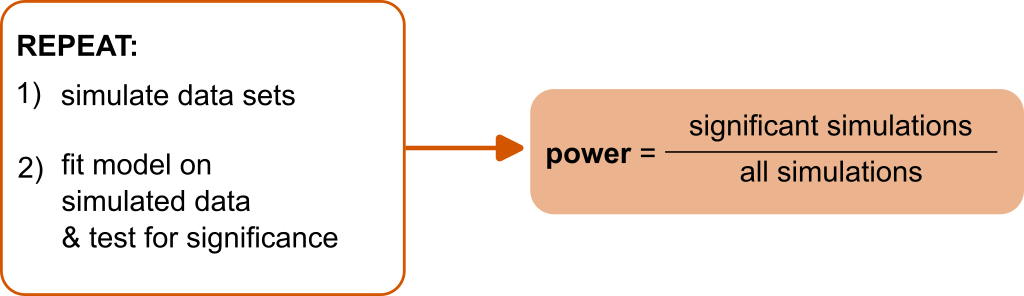

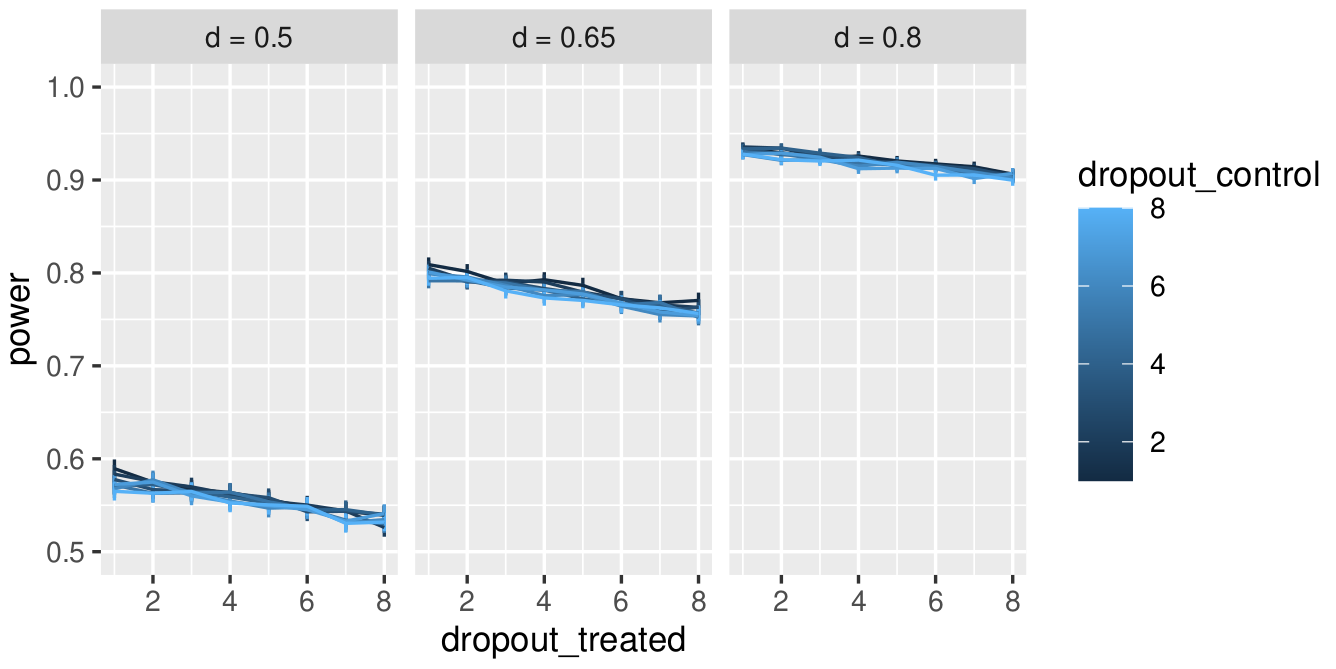

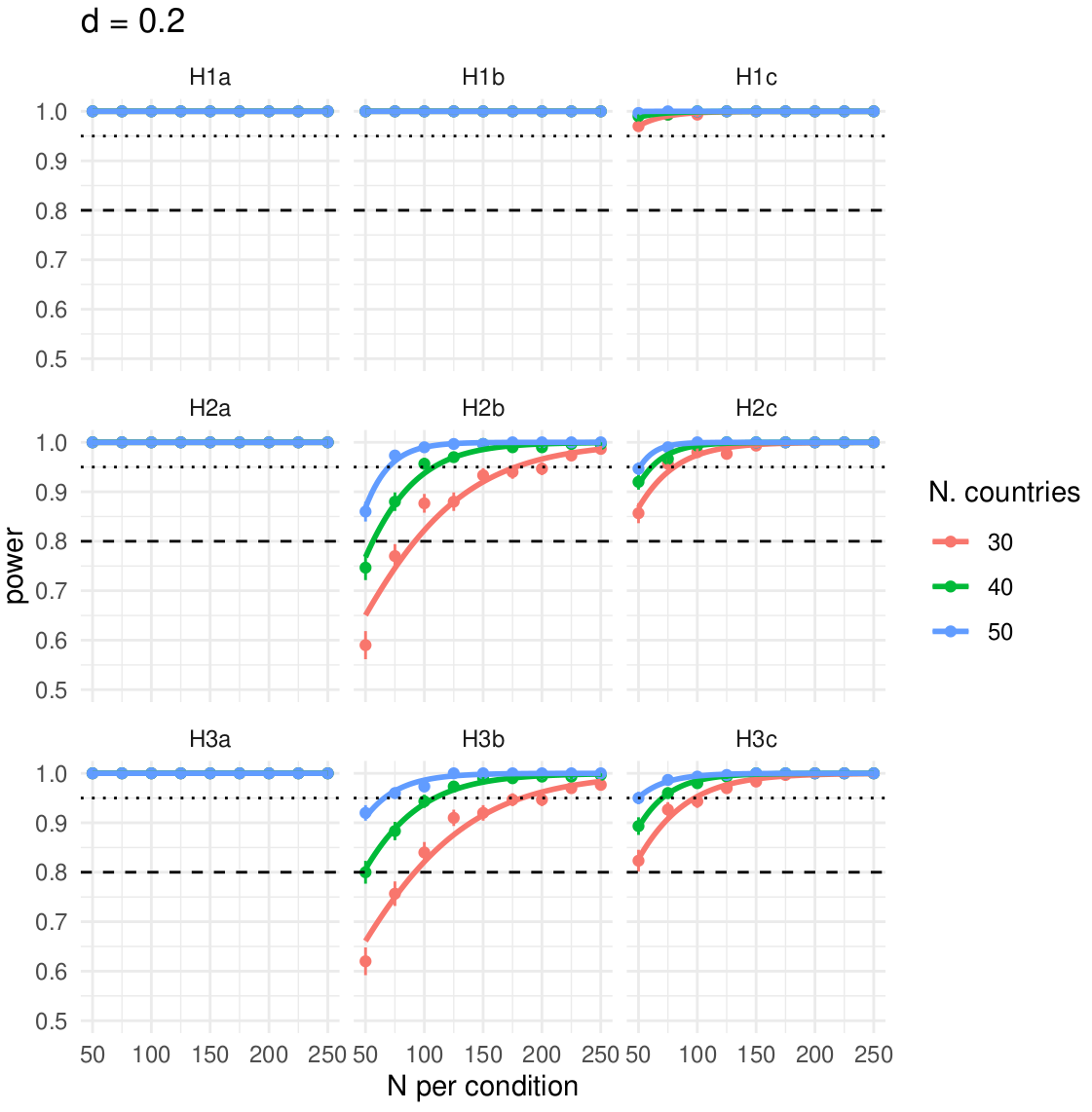

class: title-slide, center, inverse # Power analyses via data simulation # ## Matteo Lisi ### 15 November 2023 --- ## Outline 1. key concepts. 2. Simulation approach. 3. Worked example (one-way ANOVA with 3 means). 4. Multiple hypothesis tests. 5. Case studies. --- ## Power Analysis Basics - **Statistical Power:** Probability that a test correctly rejects a false null hypothesis. -- - **Effect Size:** Quantitative measure of the magnitude of an effect. --- ## Key notations and meanings | Notation | Meaning | |:---------:|:------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------| | `\(\beta\)` | Probability of a Type II error (false negative) | | `\(1-\beta\)` | Probability of a true positive (correctly rejecting the null hypothesis), or **statistical power** | | `\(\alpha\)` | Probability of a Type I error (false positive) | | `\(1-\alpha\)`| Probability of a true negative (correctly not rejecting the null hypothesis) | --- ## Key notations and meanings <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-1-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- Example of power curve for a paired t-test with N=30, using the `pwr` library. .pull-left[ ```r library(pwr) # Define parameters d <-c(0.2,0.5,0.8) N <- seq(15, 200, 1) alpha <- 0.05 # Calculate power for each effect size X <- expand_grid(d, N) power<-with(X, pwr.t.test(d = d, n = N, sig.level = alpha, type = "paired")$power) # Plot X %>% mutate( d = ordered(d)) %>% ggplot(aes(x=N,y=power, color=d))+ geom_hline(yintercept = 0.8, linewidth=0.4, lty=2)+ geom_line(linewidth=1.5)+ scale_x_continuous(breaks=seq(0,300,25))+ labs(y="Power (1 - β)", x="Sample size (N. participants)") ``` ] .pull-right[ <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-3-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- name: eff_size # Effect sizes -- - A summary statistics that capture the _direction_ and _size_ of the "effect" of interest (e.g. the mean difference between two conditions, groups, etc.) -- - _Unstandardized_ vs. _standardized_ -- - Example: standardized mean difference `\(\text{Cohen's }d = \frac{\text{mean difference}}{\text{expected variation of individual observation}}\)` - For two independent groups: `\(\text{Cohen's }d = \frac{{\overline{M}}_{1}{-\overline{M}}_{2}}{\text{SD}_{\text{pooled}}}\)` --- ## Statistical power - Probability that a test correctly rejects a false null hypothesis. - Power ( `\(1-\beta\)` ) is a property of a statistical test -- - For simple tests can be computed exactly. -- - More complex situations (i.e. already 2-way ANOVA) are easier to approach using simulations <!-- --- --> <!-- ## Limitations of Analytical Formulae to calculate `\(1-\beta\)` --> <!-- - Formulas available only for basic designs. --> <!-- -- --> <!-- - Already for 2-way ANOVA, especially for imbalanced designs, the calculation can get quite involved. --> <!-- -- --> <!-- - For ANOVA with >2 means, power is sensitive to the pattern of means. --> <!-- -- --> <!-- - Often no closed-form solutions for more complex situations involving "random effects" or more complex models (e.g. multiple logistic or ordinal regression). --> <!-- -- --> <!-- - Standard approaches based on analytical calculations do not allow to take real-world complexities into account (e.g. data may not be perfectly normal, or not have homogenous variance) --> --- class:inverse ## Simulation approach - Simulation is useful because allows creating a _ground truth_ by which to test our study design. -- - In the simulation the true process by which the data are generated is known and we can check whether our models and study design are doing well at recovering this truth. -- - Simulating data helps us model real-world scenarios more closely (things like attrition, etc. can be included in the simulation). --- name: power ## Simulation approach (in 1 figure) -- .center[] --- class: inverse ## Basics of data simulation - R has some useful functions for generating data randomly drawn from different distributions. -- - Random generation function usually have the `r` prefix, for example: - `rnorm()` for normal distribution - `rbinom()` for binomial distribution -- - To see all distributions available in the `stats` package (included in R installation by default) type `?Distributions` --- .pull-left[ Uniform distribution from 0 to 1 ```r N <- 1000 unifSamples <- runif(N, min = 0, max = 1) hist(unifSamples) ``` <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-5-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] -- .pull-right[ Normal distribution with mean 5 and standard deviation 1 ```r normSamples <- rnorm(N, mean = 5, sd = 1) hist(normSamples) ``` <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-6-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- .pull-left[ Binomial distribution, 10 trials with success probability 0.25 ```r binomSamples <- rbinom(N,size=10, prob=0.25) hist(binomSamples) ``` <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-7-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] -- .pull-right[ Student’s t distribution with 4 degrees of freedom ```r tSamples <- rt(N, df =4) hist(tSamples) ``` <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-8-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- #### Simulating Multivariate Normal Data For simulating multiple, possibly correlated variables the procedure is slightly more involved as it requires setting the correlation between variables. -- <br> <!-- --> --- **Example: 2 correlated normal variables:** -- .pull-left[ 1) <u> Define standard deviations and correlations </u> - `\(\sigma_1\)` and `\(\sigma_2\)`: standard deviations - `\(\rho\)`: Pearson correlation coefficient ```r # Given values sigma1 <- 2 sigma2 <- 3 rho <- 0.5 ``` ] -- .pull-right[ 2) <u> Construct the 2x2 variance-covariance matrix </u> - `\(\mathbf{\Sigma} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \sigma_1^2 & \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \rho \\ \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \rho & \sigma_2^2 \end{array} \right]\)` ```r # Build variance-covariance matrix sigma<-matrix(c(sigma1^2, rho*sigma1*sigma2, rho*sigma1*sigma2, sigma2^2), 2, 2) print(sigma) ``` ``` ## [,1] [,2] ## [1,] 4 3 ## [2,] 3 9 ``` ] --- .pull-left[ 3) Multivariate normal data can then be simulate with the `mvrnorm()` function (included in the `MASS` package) ```r library(MASS) # load library data<- mvrnorm(N, mu = c(0,0), # means Sigma = sigma) head(data) ``` ``` ## [,1] [,2] ## [1,] 0.5177270 0.7480858 ## [2,] -1.5358257 0.8427981 ## [3,] -0.3983506 3.1190832 ## [4,] -0.6834584 -1.1529971 ## [5,] 0.4347450 -0.7484723 ## [6,] 0.9078966 -1.0471776 ``` ] -- .pull-right[ Plotting results ```r ggplot(as.data.frame(data), aes(x = V1, y = V2)) + geom_point(alpha = 0.5) + labs(x = "Variable 1", y = "Variable 2") ``` <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-13-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- ### Example: simulate data for a basic one-way ANOVA .pull-left[ We assume 3 independent groups, each with 30 participants and different means. ```r # Simulate data group1 <- rnorm(30, mean = 50, sd = 10) group2 <- rnorm(30, mean = 52, sd = 10) group3 <- rnorm(30, mean = 55, sd = 10) data <- data.frame( value = c(group1, group2, group3), group = factor(rep(1:3, each = 30)) ) head(data) ``` ``` ## value group ## 1 44.39524 1 ## 2 47.69823 1 ## 3 65.58708 1 ## 4 50.70508 1 ## 5 51.29288 1 ## 6 67.15065 1 ``` ] -- .pull-right[ Visualize simulated dataset: <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-16-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- class:inverse ### Example: simulate data for a basic one-way ANOVA Given our chosen means and SD, what is the standardized effect size? .pull-left[ `\(\text{Cohen's} f\)` is defined as _the standard deviation of the group means divided by the pooled standard deviation_: ```r M_i <- c(50, 55, 52) # means sqrt( sum((M_i - mean(M_i))^2)/3 ) / 10 ``` ``` ## [1] 0.2054805 ``` ] -- .pull-right[ Book source for formulas: .center[] ] --- ### Example: simulate data for a basic one-way ANOVA We can analyse simulated data in the same way as we would do with real data ```r anova_res <- aov(value ~ group, data) summary(anova_res) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## group 2 529 264.49 3.284 0.0422 * ## Residuals 87 7008 80.55 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` -- To compute the power of our design, we need to iterate this procedure for thousands of times and count how frequently the ANOVA turns out significant. -- A good way to approach this is to write 2 _custom R functions_: one that simulates the data, and one that run the statistical test. --- class:inverse ### Writing a Custom Function in R 1. Use the `function` keyword. 2. Specify the function arguments inside parentheses. 3. Provide the operations or calculations in `{}`. <br> Example: ```r # Example function to add two numbers add_numbers <- function(a, b) { result <- a + b return(result) } # Use the function add_numbers(3, 4) ``` ``` ## [1] 7 ``` --- ### Data simulation function for one-way ANOVA example ```r simulate_data <- function(N_per_group){ group1 <- rnorm(N_per_group, mean = 50, sd = 10) group2 <- rnorm(N_per_group, mean = 52, sd = 10) group3 <- rnorm(N_per_group, mean = 55, sd = 10) data <- data.frame( value = c(group1, group2, group3), group = factor(rep(1:3, each = N_per_group)) ) return(data) } ``` --- ### Function that run one-way ANOVA and return p-value ```r run_test <- function(data){ summary_result <- summary(aov(value ~ group, data)) p_value <- summary_result[[1]]["group","Pr(>F)"] return(p_value) } ``` -- These functions can be nested into a single line of code: ```r run_test(simulate_data(30)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.01900815 ``` --- ### Compute power for a single sample size .pull-left[ Iterate simulation and testing for 1000 simulated datasets, each with N=30 participants per conditions ```r N_sim <- 10^3 p_values <- rep(NA,N_sim) # run simulations on a loop for(i in 1:N_sim){ p_values[i]<-run_test(simulate_data(30)) } ``` Power is the fraction of significant results ```r alpha <- 0.05 mean(p_values < alpha) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.364 ``` ] -- .pull-right[ ```r hist(p_values, breaks=20) ``` <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-25-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- count: false ### Compute power for a single sample size .pull-left[ Iterate simulation and testing for 1000 simulated datasets, each with N=30 participants per conditions ```r N_sim <- 10^3 p_values <- rep(NA,N_sim) # run simulations on a loop for(i in 1:N_sim){ p_values[i]<-run_test(simulate_data(30)) } ``` Power is the fraction of significant results ```r alpha <- 0.05 mean(p_values < alpha) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.376 ``` ] -- .pull-right[ <u>How does this compare to analytical calculation?</u> ```r # compute cohen's f M_i <- c(50, 55, 52) f <- sqrt(sum((M_i - mean(M_i))^2)/3) / 10 # compute power pwr.anova.test(k=3, n=30, f=f, sig.level=0.05) ``` ``` ## ## Balanced one-way analysis of variance power calculation ## ## k = 3 ## n = 30 ## f = 0.2054805 ## sig.level = 0.05 ## power = 0.385042 ## ## NOTE: n is number in each group ``` ] --- ### Test multiple sample sizes In order to see how many participants we need, we can repeat the process for varying sample sizes, and see at which point the fraction of significant results exceed our desired statistical power (e.g. 80%). ```r # sample sizes N <- seq(30, 100, 10) # N. simulated datasets per sample size N_sim <- 10^3 # pre-allocate in a table simres <- expand_grid(iteration=1:N_sim, N=N) str(simres) ``` ``` ## tibble [8,000 × 2] (S3: tbl_df/tbl/data.frame) ## $ iteration: int [1:8000] 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 ... ## $ N : num [1:8000] 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 30 40 ... ``` ```r simres$p <- NA for(i in 1:nrow(simres)){ simres$p[i] <- run_test(simulate_data(simres$N[i])) } ``` --- ### Test multiple sample sizes Visualize results: .pull-left[ ```r # custom function to compute binomial SE binomSE <- function (v) { sqrt((mean(v) * (1-mean(v)))/length(v)) } # make plot simres %>% group_by(N) %>% summarize(power = mean(p<alpha), se = 2*binomSE(p<alpha), exact=pwr.anova.test(k=3, n=N, f=f, sig.level=alpha)$power) %>% ggplot(aes(x=N, y=power))+ geom_errorbar(aes(ymin=power-se, ymax=power+se), width=0)+ geom_point()+ geom_line(aes(y=exact), color="blue") ``` ] .pull-right[ <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-31-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- class:inverse ### Multiple hypothesis tests - Power calculation in the ANOVA example depended on the group effect's significance. -- - A significant group effect suggests at least one mean difference. -- - However, the .orange[hypothesis might specify multiple significant differences] (e.g. 2 treatment groups both predicted to be higher than controls; or 2 experimental manipulations that are predicted to move up or down the group means). -- - In the example, such tests would not be independent because they share a common control, leading to correlated variability in statistics. -- - For registered reports, it's critical to ensure the study design can powerfully test all relevant comparisons specified in the hypothesis. --- class:inverse ### Multiple hypothesis tests - More in general, whenever we have multiple tests/outcomes there is more than one definition of statistical power: - **individual power** power for individual tests considered separately - **_d_-minimal power** power of observing at least _d_ significant results out of all the tests conducted <a name=cite-Porter2018></a>([Porter, 2018](https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2017.1342887)) - **complete power** probability of simultaneously rejecting all null hypotheses (assuming they are all false). Also referred to as 'conjunctive power' or 'all pairs power' <a name=cite-Ramsey1978></a>([Ramsey, 1978](https://www.jstor.org/stable/2286584)) -- <br> In our example, for example our hypothesis may predict two differences: - .orange[`group1` < `group2`] - .orange[`group3` > `group2`] ```r group1 <- rnorm(N_per_group, mean = 50, sd = 10) group2 <- rnorm(N_per_group, mean = 52, sd = 10) group3 <- rnorm(N_per_group, mean = 55, sd = 10) ``` --- ## Complete power simulation ```r run_test <- function(data){ # anova anova_summary <- summary(aov(value ~ group, data)) p_value_aov <- anova_summary [[1]]$`Pr(>F)`[1] # planned comparison p_value_t1 <- t.test(data$value[data$group=="1"], data$value[data$group=="2"], alternative="less")$p.value p_value_t2 <- t.test(data$value[data$group=="2"], data$value[data$group=="3"], alternative="less")$p.value # return p-values as a named vector res <- c(p_value_aov, p_value_t1, p_value_t2) names(res) <- c("aov", "1<2", "2<3") return(res) } ``` --- count: false ## Complete power simulation ```r # settings N <- seq(30, 300, 10) N_sim <- 10^4 # pre-allocate simres <- expand_grid(iteration=1:N_sim, N=N) simres$p_aov <- NA simres$p_1vs2 <- NA simres$p_2vs3 <- NA # run simulations for(i in 1:nrow(simres)){ res <- run_test(simulate_data(simres$N[i])) simres$p_aov[i] <- res['aov'] simres$p_1vs2[i] <- res['1<2'] simres$p_2vs3[i] <- res['2<3'] } ``` --- count: false ## Complete power simulation <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-36-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- count: false ## Complete power simulation Correlations between p-values <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-37-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: inverse ## Power and multiple tests: discussion - When you have multiple comparison as part of one hypothesis, it is important to specify .orange[whether all tests need to be significant to claim that the hypothesis is supported by the data] -- - For complete power, controlling for multiple comparison is not necessary. This is because the probability that all tests result in Type 1 error is smaller than the probability that any single test alone would result in a Type 1 error. --- #### Correlation between tests For 2 independent events `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` `$$p(A \cup B) = p(A) \times p(B)$$` If we have two _independent_ tests, each with Type 1 error probability set to `\(\alpha=0.05\)`, then the probability that both give a false positive is $$ \alpha \times \alpha = 0.05^2 = 0.0025$$ which is already smaller than the Bonferroni corrected threshold for 2 comparisons, `\(\frac{\alpha}{2}=0.025\)` -- <br> <br> (This has implication also for power: if the individual power for each _independent_ test is `\(0.8\)`, then the _complete_ power is `\(0.8^2=0.64\)`.) --- #### Correlation between tests Correlation between tests can increase false-positive rates! <img src="power_analyses_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-38-1.svg" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: inverse ## Power and multiple tests: discussion - When you have multiple comparison as part of one hypothesis, it is important to specify .orange[whether all tests need to be significant to claim that the hypothesis is supported by the data] - For complete power, controlling for multiple comparison is not necessary. This is because the probability that all tests result in Type 1 error is smaller than the probability that any single test alone would result in a Type 1 error. -- - For _d_-minimal power, it may be necessary to control for multiple comparisons (typically using FWER procedures) --- # Multiple comparisons - **Familywise error rate (FWER)** procedures, e.g. Bonferroni, ensure the probability of at least one Type 1 error across all tests is `\(<\alpha\)` - **False discovery rate (FDR)**, e.g. Benjamini & Hochberg, ensure the expected proportion of erroneously rejected null hypotheses is `\(<\alpha\)` -- <br> <br> FWER procedures can be further distinguished also depending on whether they _weak_ or _strong_ control. - _strong_ control means that error rate is controlled also in cases when some null are true and some are false (e.g. Bonferroni, Holm-Bonferroni provide strong control of FWER); - _weak_ control means that the error rate is controlled only in the idealized case where all null hypotheses are true (e.g. Fisher's least significant difference with >3 means) --- ## Power and multiple tests: summary Think carefully about hypotheses: what pattern of statistical results would support them? -- - If only 1 test is conducted, no further adjustment needed. -- - If 1 test out of several is sufficient, then correction for multiple comparison should be included in the simulation (typically FWER). -- - If all tests needs to be simultaneously significant, no correction needed. -- - If only `\(d\)` out of `\(n\)` tests are sufficient, then "it's complicated": it depends on the context, number of tests, etc. Correction for multiple comparisons may be required, although less stringent ones (FDR) may work better. --- ### Case study 1: accounting for dropouts - N=25 patients (young children) undergoing gene therapy (patients are rare, so impossible to increase N for this group) - N=50 age-matched controls - 2 measurement sessions for each participants (averaged together to improve precision) -- _What happens if a patient or a control drop-out and misses the second measurement?_ --- count: false ### Case study 1: accounting for dropouts Simulation results, assuming a correlation of `\(\rho=0.5\)` between individual measurements. .center[] --- ### Case study 2: Psychological Science Accellerator proposal - 2-phases Cognitive Reflection tests: participants are given 6 CRT problems (e.g. "bat & ball problem") to answer under time pressure in phase 1, and given opportunity to correct their responses in phase 2. - The dependent variable is `\(p(\text{corrected} | \text{error})\)`, so the n. of observations per participants depends on the errors they make, and is analyzed with multilevel logistic regression. - Some hypotheses involves comparison between cultural clusters, but number of participating labs/countries not known in advance. --- count: false ### Case study 2: Psychological Science Accellerator proposal .left-column[ Realistic simulation, simulating error rates based on available literature. Effect sizes were set to small (Cohen's `\(d\)`=0.2) and transformed to log-odds units by multiplying `\(d\)` by the SD of the standard logistic distribution `\(\frac{\pi}{\sqrt{3}}\)`. ] .right-column[ .center[] ] --- ## References <a name=bib-Porter2018></a>[Porter, K. E.](#cite-Porter2018) (2018). "Statistical Power in Evaluations That Investigate Effects on Multiple Outcomes: A Guide for Researchers". In: _Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness_ 11.2, pp. 267-295. DOI: [10.1080/19345747.2017.1342887](https://doi.org/10.1080%2F19345747.2017.1342887). <a name=bib-Ramsey1978></a>[Ramsey, P. H.](#cite-Ramsey1978) (1978). "Power Differences Between Pairwise Multiple Comparisons". In: _Journal of the American Statistical Association_ 73.363, pp. 479-485. URL: [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2286584](https://www.jstor.org/stable/2286584).